‘Us kids swim off a gray pier, dive off’

(Jack Kerouac,‘Dream’)

As a boy growing up in the English coastal town of Cleethorpes, the area of open land beyond the footbridge that crossed the railway line at the end of Fuller Street was a space for exploration. Beyond the railway sidings, separated from the track by an old chicken wire fence, was an area of uneven green land, the sea defences and, further beyond that, the beach; not the neat, tidy beach presented to the daytrippers who clambered off the trains which pulled into Cleethorpes railway station near the promenade, but a utilitarian beach peppered with rocks and objects that had presumably fallen from the decks of the cargo ships and ferries that entered, and exited, the Humber estuary, before washing ashore. It was the beach of the locals rather than the beach of the tourists or outsiders. People would call it ‘wasteground’ but to us kids, it was a place of possibilities. I would walk our family dog there, or walk with my friends as they walked their pet dogs. My friends and I would take our bicycles and ride up the mounds, freewheeling down the other side. We would play football and other games, pretending that the open land was a battleground and we were soldiers. We would dare each other to climb the dangerous-looking structure that overlooked the railway lines, ascending to a platform via a rusty ladder. I would jump off the sea defences, oblivious in my naïve youth to the danger that was presented by the narrow but steep stepped wall below, made perpetually slick by the presence of wet seaweed. It could be a place of solitude, where one went to find quiet and peace of mind. I was told that my grandmother embarrassed the local ‘flasher’ there by laughing at what he had put on display, and from the wasteground one could see the house in which my father and his family had lived, in Harrington Street, when they moved to Cleethorpes in the 1960s.

Standing on the wasteground, looking across the railway lines that carried tourists to their seaside destination, the stadium lights belonging to the home of Grimsby Town Football Club rose above the dilapidated late Victorian terraced houses where some of my friends lived. For some of these boys, the possibility of a career as a professional footballer with GTFC was their dream escape from the reality of a proletarian existence, an alternative to the downtrodden wage-slavery that was, for most of us, our most likely future; that is, for those of us who made it into adulthood and found our lives not blighted – or destroyed – by the dark and hidden realities of our childish lives within the English working class. One schoolmate of mine was beaten so badly by his father that the injuries followed him into adulthood and ultimately contributed to his early death before the age of 30; a number of my schoolmates succumbed to the anomie of life in a town that held little future for them, taking solace in the ready availability of heroin in Grimsby and Cleethorpes during the 1980s and 1990s, finding temporary bliss in a drug which ultimately took the lives of a notable number of the boys with whom I went to school. One of my best friends lived an intolerable life at home and an almost equally intolerable life at school, where he was labelled as a bad apple and shouldered the blame for everything that could be thrown his way by the teachers. He went on to serve his country during the Second Gulf War, returning with PTSD that no doubt contributed to several run-ins with the police, before finding some comfort in writing poetry.

As an adolescent, I would often walk on this ground with girls who would become friends or lovers. I vividly remember during the spring of one year, parts of the sea wall were covered with ladybirds that moved en masse, giving the impression of a carpet of red and black.

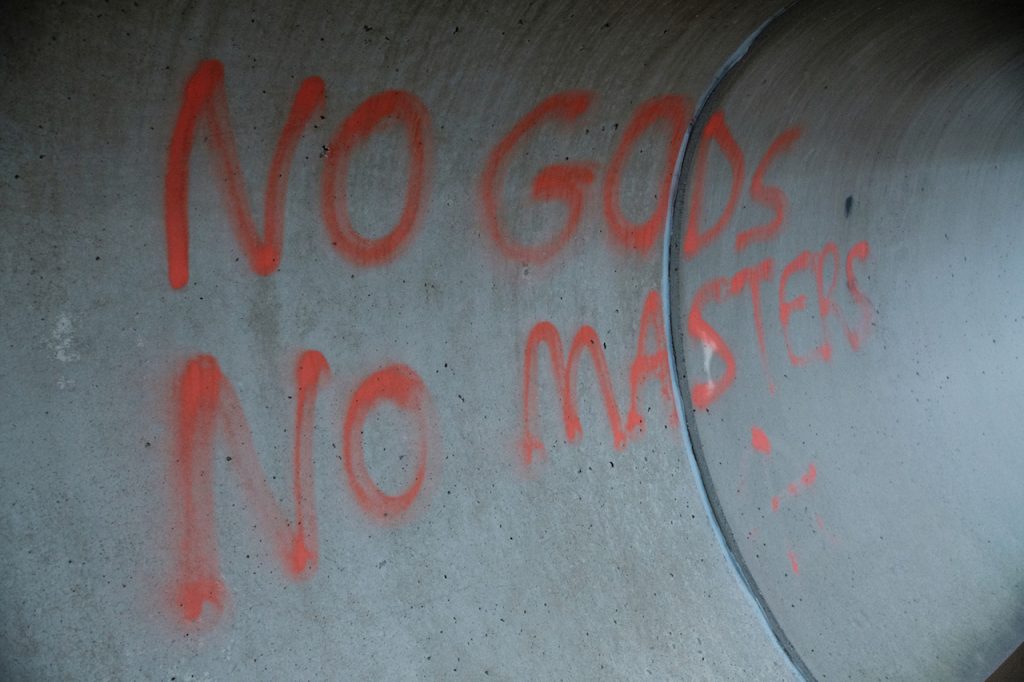

At some point in my young adulthood, in 1996 or 1997, most of the wasteground was fenced off by Associated British Ports, who claimed ownership of the land, earmarking it for development and restricted access to it, blocking a number of public rights of way – though to this day, many locals contest ABP’s claim and continue to find ways to access this plot. ABP wish to ‘develop’ the land, which as local residents have asserted, would be harmful to the species of wildlife – some of it endangered – that one can encounter there. I have seen deer on this land; gulls, sandpipers and robins can be found there at various points in the year. Now, whether it is due to change or simply evolution of my own temperament, the area seems quiet and bleak. Graffiti adorns the seawall, some of it meaningful, some of it artistic, and some of it utterly redundant. Shopping trolleys stolen from local supermarkets are abandoned there, as are television sets, mattresses and unwanted items of furniture. Fires have been started, small encampments of homeless people dot the landscape as in a Hollywood film about inner city Detroit or a camp filled with refugees from the future. The promise has gone; the potential ebbed away. Or was it always such?