The following is the full text of an interview I conducted via email with the superb fine art/documentary photographer and photojournalist Shannon Taggart, whose inspirational work focuses on spiritualism and the ethereal, back in 2016. The interview was conducted as part of my preparation for an article and conference paper focusing on spirit photography and the lasting impact of its visual paradigms on depictions of the supernatural and the liminal in both still and moving image photography. Shannon’s Instagram page is a fascinating repository for Shannon’s own photographic work and archival imagery on the subject.

A promo video for Shannon’s book Seance (2019) can be found at this link. Seance, available from the 26th of November, can be purchased from Amazon and other retailers.

I am as always very grateful to Shannon for taking time to answer my questions so thoughtfully.

QUESTION: How cognisant of the work of the pioneering spirit photographers of the 19th and early 20th Centuries (such as William Mumler and William Hope) are you when producing your own work? Do you allow the paradigms associated with their photography to shape your own work consciously and directly? How would you describe the relationship between their work and your own?

QUESTION: How cognisant of the work of the pioneering spirit photographers of the 19th and early 20th Centuries (such as William Mumler and William Hope) are you when producing your own work? Do you allow the paradigms associated with their photography to shape your own work consciously and directly? How would you describe the relationship between their work and your own?

SHANNON: Spirit photography was not acknowledged in any of the official photography text books I studied from. When I began my project on Spiritualism in 2001, I had never even heard of spirit photography. Unexpectedly, the Spiritualists I met introduced me to it. I soon became enthralled with this secret history. I was shocked by spirit photographs. I was dumbstruck by their absurdity, their outrageousness, and their odd humanity. And their tenderness. And how the images spoke so eloquently about grief, about love and loss. This hidden photographic history then became a resource and an inspiration for my own photographic theory and practice.

QUESTION: Your work differs from that of the spirit photographers of the 19th/early 20th Centuries by, obviously, featuring a mixture of both colour and monochrome photography. You suggest in the statement on your website that in Spiritualism, technology is used to ‘extend the senses and assist an engagement with the spirit world’. Do you feel that the camera has a similar function? What determines your choice of medium/photographic equipment? What equipment do you use? Do you find that the choice of medium (for example, the film/digital distinction) is important? How does it impact on your work?

SHANNON: Yes, photography is one of the many technologies that Spiritualists use to extend the senses and invoke the unseen. I have been inspired by some of these approaches, which are part of the current “instrumental-transcommunication” movement within Spiritualism. In my opinion, the specific camera, film, or digital chip used makes little difference. I have shot with a variety of gear, and I have tried numerous types of film and digital backs.

I began to play with the glitches inherent within the photographic process after accidentally creating synchronistic photographs. One example happened during a séance, when people claimed to see a woman’s doppelgänger floating peacefully next to her. I did not see this. I attempted to make a straight document of the event, but her doubled face appeared on my film. I found this surprise thrilling—my camera shutter rendered a perfect metaphor for the invisible experience.

I became interested in exploring this photographic synchronicity. I tried conventions that are considered wrong, messy or “tricky”, breaking the rules of what is considered technically correct or professional. I saw how photography’s accidents and errors seemed to offer a visual language for the immaterial. I began to think about the magic of using light, time and automation as raw materials. I began to consider the conjuring power of photography itself.

My work blurs the distinctions between ethnographic study, photojournalism, and art. My goal is to produce a project that informs, but one that also blurs boundaries and creates questions. I do this by including images that use photography’s own mechanisms to question these spiritual realities–photographs that contain both mechanical and spiritual explanations, requiring interpretation.

QUESTION: As you suggest in the statement on your website, ‘The answer came when I pushed my camera to the edge of its functionality and crossed the boundary of what is considered bad, wrong or unprofessional. Chance elements and the inherent imperfections of the photographic process (blur, abstraction, motion, flare) offer an agent for the immaterial’. Are these ‘chance elements’ the same in today’s world of digital photography as they were in, say, Mumler’s use of photographic plates; or do you feel there is a qualitative difference between the ‘chance elements’ of digital photography and those of the photography of the 19th/early 20th Centuries?

SHANNON: The difference between then and now is that we understand photography’s subjective abilities better. We understand trick photography, accidents, and double exposure. Despite this knowledge, the photographic process still retains a level of mystery that is astounding. Photography remains magical, whatever the technical process. It freezes time, it automates, it transforms. Even the most pragmatic practitioners speak of its mystery.

QUESTION: In your statement, you highlight the distinction between the ‘veiled presence’ and the ‘visible body’. Spirit photography has traditionally seen a tension between depicting the ghostly/ethereal (for example, the ‘intangible presences’ within the photography of William Mumler and William Hope) and the physical/corporeal (for example, the vogue in the 1920s for parapsychologists/photographers like Albert von Schrenck-Notzing and T G Hamilton to photograph ectoplasmic emissions). In the work of the spirit photographers of the 19th/early 20th Centuries, these two approaches very rarely crossed over – if at all. Do you think these two approaches may be reconciled? Do these two approaches communicate the sense of liminality in the same way as one another, or do they possess different connotations?

SHANNON: This tension between the intangible and the physical is still present in Spiritualism today, so it’s something I’ve struggled with while trying to create photographs of mediums. I have been unable to reconcile these approaches. The mediums who produce objective physical effects beg to be straightly documented. Their ritual acts leave no room for play–they’ve already rendered a mystery. The mediums whose workings remain invisible seem to offer a richer atmosphere for photographic interpretation and experimentation.

QUESTION: In what ways do you think our relationship with these images is similar to, or different from, how the work of photographers like William Hope or Albert von Schrenck-Notzing was received during the 19th/early 20th Centuries? Do you think the 19th Century emphasis that was placed on photography as ‘evidence’, which formed a large part of the context of the work of photographers like Mumler and Hope – with photography used as ‘proof’ by both Spiritualists and skeptics – is still with us today?

SHANNON: Albert von Schrenck-Notzing came to conclude that “a photograph reproduces only an instant, abstracted from the flow of the living event as it occurred during seances. For this reason, the effect it produced could only be crude and deceptive.” He abandoned the photographic process for its inability to render what he saw as objective fact. He recognized that photographs complicated truth. I see myself as embracing the process for the exact reasons that Schrenck-Notzing abandoned it. I’m trying to take photography’s innate subjectivity as far as it will go, to see what will happen. That said, I do find that many viewers don’t take into account the complexity of a photographic truth. This is a theme I try to address every time I lecture. Photography is a trickster medium. Photographs continually offer a variety of interpretations. And this invitation to assign meaning is a major part of photography’s power.

SHANNON: Albert von Schrenck-Notzing came to conclude that “a photograph reproduces only an instant, abstracted from the flow of the living event as it occurred during seances. For this reason, the effect it produced could only be crude and deceptive.” He abandoned the photographic process for its inability to render what he saw as objective fact. He recognized that photographs complicated truth. I see myself as embracing the process for the exact reasons that Schrenck-Notzing abandoned it. I’m trying to take photography’s innate subjectivity as far as it will go, to see what will happen. That said, I do find that many viewers don’t take into account the complexity of a photographic truth. This is a theme I try to address every time I lecture. Photography is a trickster medium. Photographs continually offer a variety of interpretations. And this invitation to assign meaning is a major part of photography’s power.

QUESTION: Do you think the visual paradigms/iconography of spirit photography of the 19th/early 20th Centuries have played a significant role in how the theme of liminality has been explored in other areas of visual culture of the 20th/21st Centuries (for example, in films about ghosts, etc)? If so, in what ways?

SHANNON: In contemporary culture, there is an awareness of Spiritualist photographic iconography that is disconnected from its history. Ectoplasm, Spiritualism’s most iconic symbol, is part of a shared visual vocabulary, demonstrated from jokes on the cartoon South Park to imagery used by fine artists like Mike Kelley and Tony Oursler. Most famously, ectoplasm appears in the 1984 movie Ghostbusters, co-written by Dan Ackroyd, and soon to be in theaters as a sequel film. Dan Ackroyd is a fourth generation Spiritualist, and he is drawing the term directly from Spiritualist practice. These examples attest to the power of this imagery, and also to its marginalization.

QUESTION: What do you feel is the reason for the enduring fascination with this theme of liminality within visual culture? Why is it so prevalent? Are the reasons for its appeal today the same as for its appeal during the early years of spirit photography?

The liminal realm is where all myth and mystery reside. This visualized liminality, with its blurring of the true and the false, flickers so intensely that it’s difficult to take your eyes off of it. The appeal of liminality within visual culture remains because it offers a way to contemplate the ineffable within our ordered, rationalized, and largely disenchanted world.

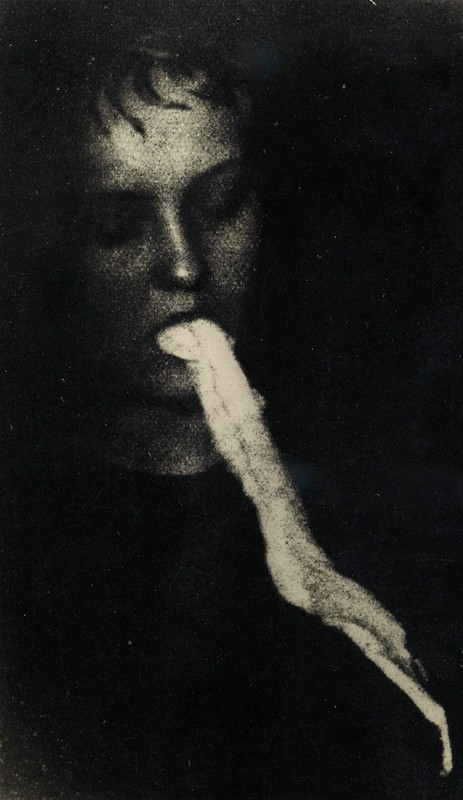

(The images used to illustrate this interview are by William Mumler and Albert von Schrenck-Notzing, respectively.)