Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Andy Milligan

Abel Ferrara

Pier Paolo Pasolini

Takeshi Kitano

Pete Walker

Sam Fuller

John Cassavetes

Satyajit Ray

Sam Peckinpah

Charles Burnett

(Okay, then, slightly more than ten 😉 .)

Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Andy Milligan

Abel Ferrara

Pier Paolo Pasolini

Takeshi Kitano

Pete Walker

Sam Fuller

John Cassavetes

Satyajit Ray

Sam Peckinpah

Charles Burnett

(Okay, then, slightly more than ten 😉 .)

Issue 3 of my semi-regular photography ‘zine, 24/36, is now available to download as a PDF, free, at this link.

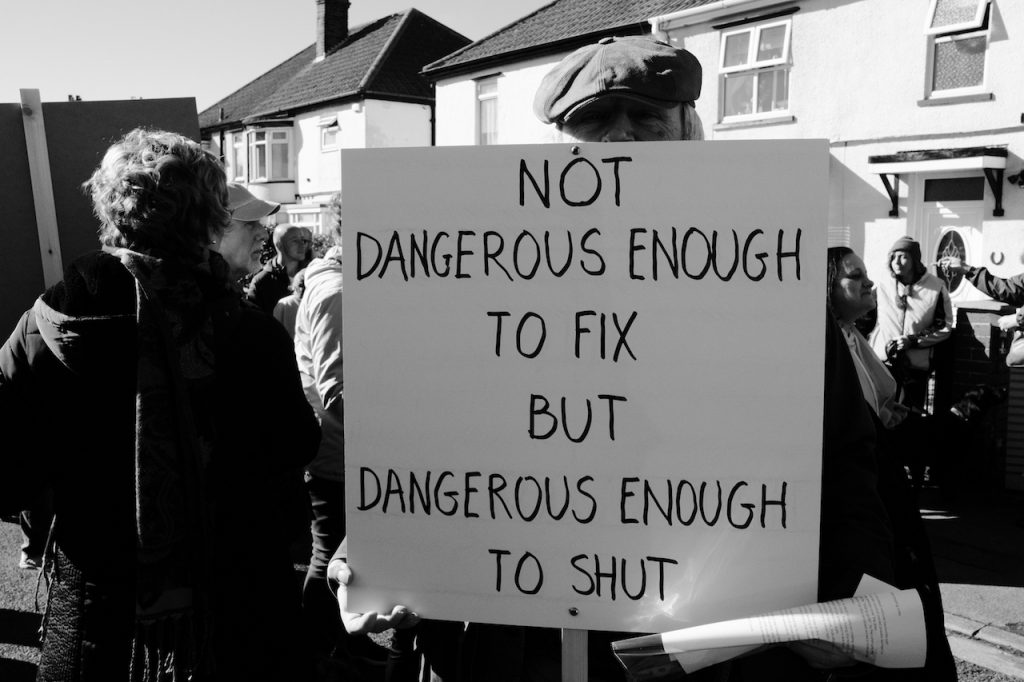

The railway crossing at the top end of Suggitt’s Lane in Cleethorpes is a lifeline for the community, offering direct access to the North Beach of Cleethorpes and, from there, the promenade. My grandmother, who lived on Suggitt’s Lane for many years, used it daily when walking her dog; my elderly father uses it daily also, as do many other local residents and, in the summer months, visitors to the coastal town.

Network Rail are planning to close this crossing, which will mean that residents will either have to climb over the steep footbridge at Fuller Street – which is impossible for many elderly, disabled or infirm persons – or make a trip of c.1.5 miles to the North Promenade, and then walk back along the North Promenade to the North Beach (another trip of 0.5-1 miles). This, again, will be difficult or nigh on impossible for many of the residents who use the railway crossing for its convenience. The planned closure of the railway crossing also raises issues for access for the emergency services, who if the crossing is closed will presumably have to access the North Beach via the promenade, which is often heavily trafficked in the summer months (apart from being a much less direct route to the North Beach itself).

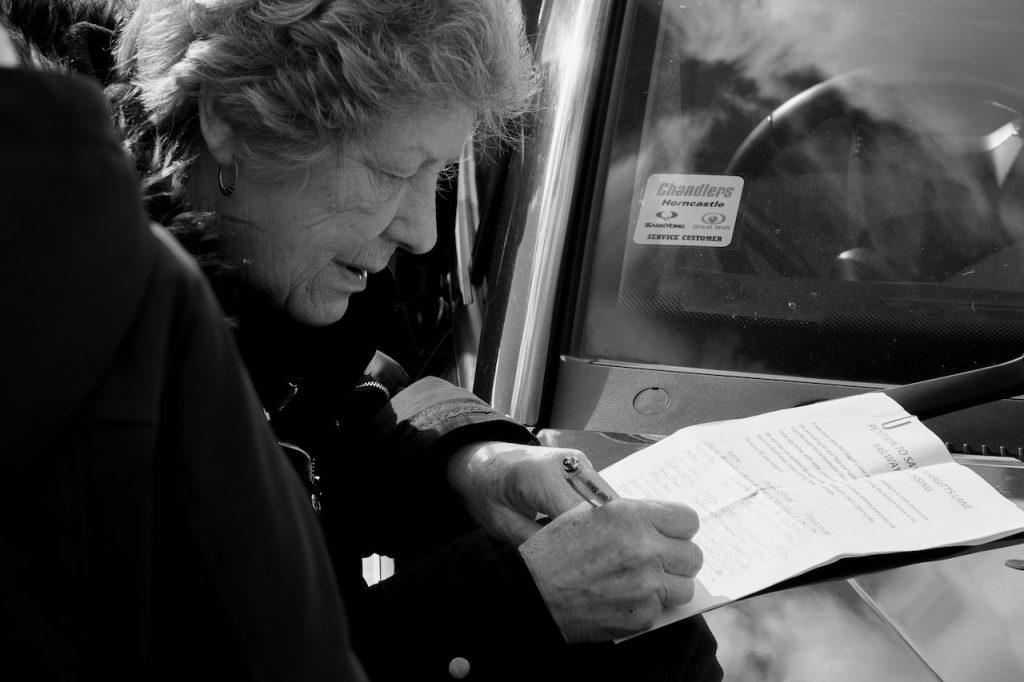

On 9 March, 2019, Friends of the North Beach organised a peaceful protest against the planned closure of the railway crossing on Suggitt’s Lane. There was a strong turnout, including Cleethorpes MP Martin Vickers and several local councillors/members of local government (including Matt Patrick and Debbie Rodwell).

More info at: https://www.facebook.com/friendsofthenorthbeach/

‘Us kids swim off a gray pier, dive off’

(Jack Kerouac,‘Dream’)

As a boy growing up in the English coastal town of Cleethorpes, the area of open land beyond the footbridge that crossed the railway line at the end of Fuller Street was a space for exploration. Beyond the railway sidings, separated from the track by an old chicken wire fence, was an area of uneven green land, the sea defences and, further beyond that, the beach; not the neat, tidy beach presented to the daytrippers who clambered off the trains which pulled into Cleethorpes railway station near the promenade, but a utilitarian beach peppered with rocks and objects that had presumably fallen from the decks of the cargo ships and ferries that entered, and exited, the Humber estuary, before washing ashore. It was the beach of the locals rather than the beach of the tourists or outsiders. People would call it ‘wasteground’ but to us kids, it was a place of possibilities. I would walk our family dog there, or walk with my friends as they walked their pet dogs. My friends and I would take our bicycles and ride up the mounds, freewheeling down the other side. We would play football and other games, pretending that the open land was a battleground and we were soldiers. We would dare each other to climb the dangerous-looking structure that overlooked the railway lines, ascending to a platform via a rusty ladder. I would jump off the sea defences, oblivious in my naïve youth to the danger that was presented by the narrow but steep stepped wall below, made perpetually slick by the presence of wet seaweed. It could be a place of solitude, where one went to find quiet and peace of mind. I was told that my grandmother embarrassed the local ‘flasher’ there by laughing at what he had put on display, and from the wasteground one could see the house in which my father and his family had lived, in Harrington Street, when they moved to Cleethorpes in the 1960s.

Standing on the wasteground, looking across the railway lines that carried tourists to their seaside destination, the stadium lights belonging to the home of Grimsby Town Football Club rose above the dilapidated late Victorian terraced houses where some of my friends lived. For some of these boys, the possibility of a career as a professional footballer with GTFC was their dream escape from the reality of a proletarian existence, an alternative to the downtrodden wage-slavery that was, for most of us, our most likely future; that is, for those of us who made it into adulthood and found our lives not blighted – or destroyed – by the dark and hidden realities of our childish lives within the English working class. One schoolmate of mine was beaten so badly by his father that the injuries followed him into adulthood and ultimately contributed to his early death before the age of 30; a number of my schoolmates succumbed to the anomie of life in a town that held little future for them, taking solace in the ready availability of heroin in Grimsby and Cleethorpes during the 1980s and 1990s, finding temporary bliss in a drug which ultimately took the lives of a notable number of the boys with whom I went to school. One of my best friends lived an intolerable life at home and an almost equally intolerable life at school, where he was labelled as a bad apple and shouldered the blame for everything that could be thrown his way by the teachers. He went on to serve his country during the Second Gulf War, returning with PTSD that no doubt contributed to several run-ins with the police, before finding some comfort in writing poetry.

As an adolescent, I would often walk on this ground with girls who would become friends or lovers. I vividly remember during the spring of one year, parts of the sea wall were covered with ladybirds that moved en masse, giving the impression of a carpet of red and black.

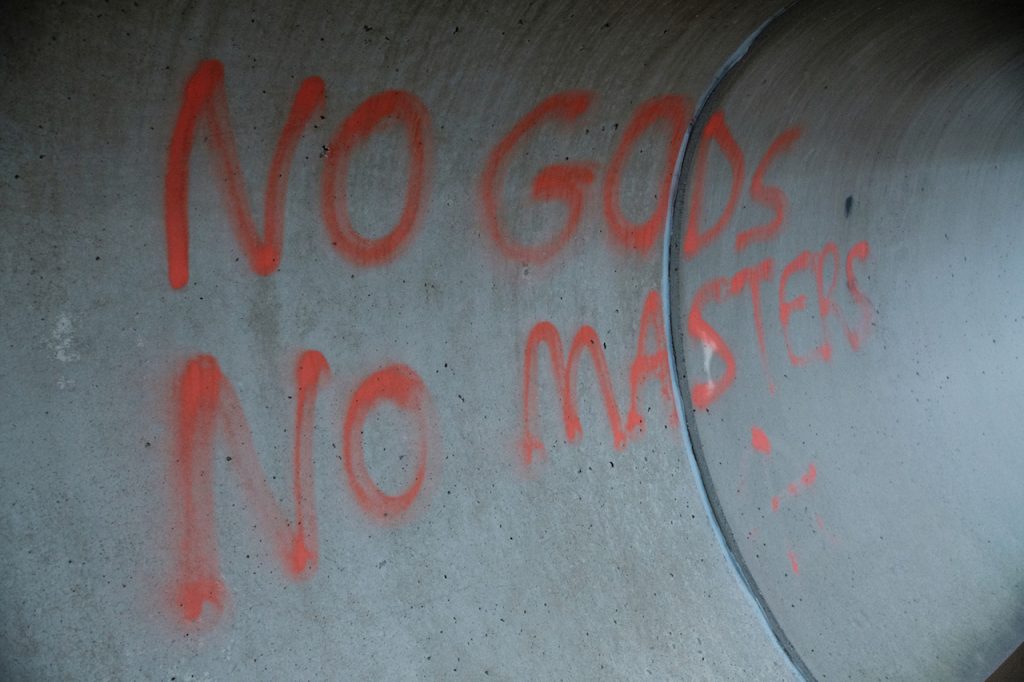

At some point in my young adulthood, in 1996 or 1997, most of the wasteground was fenced off by Associated British Ports, who claimed ownership of the land, earmarking it for development and restricted access to it, blocking a number of public rights of way – though to this day, many locals contest ABP’s claim and continue to find ways to access this plot. ABP wish to ‘develop’ the land, which as local residents have asserted, would be harmful to the species of wildlife – some of it endangered – that one can encounter there. I have seen deer on this land; gulls, sandpipers and robins can be found there at various points in the year. Now, whether it is due to change or simply evolution of my own temperament, the area seems quiet and bleak. Graffiti adorns the seawall, some of it meaningful, some of it artistic, and some of it utterly redundant. Shopping trolleys stolen from local supermarkets are abandoned there, as are television sets, mattresses and unwanted items of furniture. Fires have been started, small encampments of homeless people dot the landscape as in a Hollywood film about inner city Detroit or a camp filled with refugees from the future. The promise has gone; the potential ebbed away. Or was it always such?

Issue 2 of my photography e-zine, 24-36, is now available to download free of charge. Titled The Cathedral of the Marsh, it contains photographs of All Saints Church in Theddlethorpe. Click the PDF icon below to view/download it. Enjoy!

Issue 2 (November 2018):

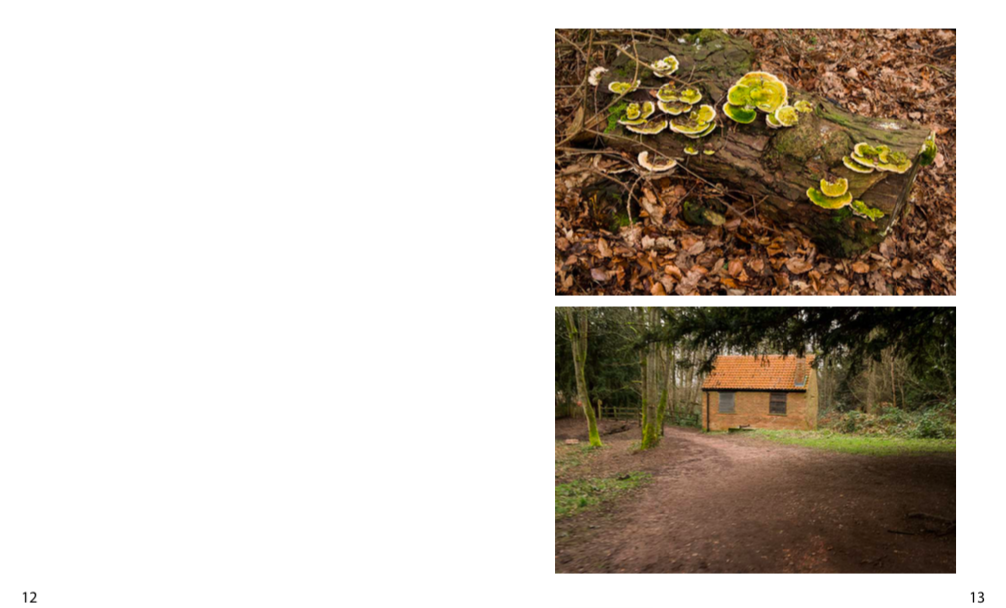

‘Black lady, black lady, I’ve stolen your baby’. Bradley Woods itself is several hundred years old, the oak trees having been planted and harvested for use in shipbuilding during the era of the Nap oleonic Wars, and stories of the Black Lady of Bradley Woods have been passed down through generations. Seen either on the road outside the woods or in the woods themselves, she is said to wear a black cloak with the hood drawn over her face. Three legends are associated with this apparition: the first suggests that she is the ghost of a nun, presumably with some association with the site of the old nunnery at Nuns Corner in Grimsby. In the second legend, the apparition is the ghost of a witch who lived in or near the woods. The third legend suggests that she is the ghost of a young woman whose husband left her to fight in either the Civil War, the War of the Roses or the Napoleonic Wars (depending on which version of the story one encounters) and, during his absence, a group of soldiers killed her infant child and raped her – either killing her or leaving her for dead. In the latter interpretation of the myth, following her encounter with the soldiers the young woman would wander the area in a black cloak, crying out for her murdered child. Say the phrase, ‘Black lady, black lady, I’ve stolen your baby’, and the Black Lady of Bradley Woods shall appear to you…

‘Black lady, black lady, I’ve stolen your baby’. Bradley Woods itself is several hundred years old, the oak trees having been planted and harvested for use in shipbuilding during the era of the Nap oleonic Wars, and stories of the Black Lady of Bradley Woods have been passed down through generations. Seen either on the road outside the woods or in the woods themselves, she is said to wear a black cloak with the hood drawn over her face. Three legends are associated with this apparition: the first suggests that she is the ghost of a nun, presumably with some association with the site of the old nunnery at Nuns Corner in Grimsby. In the second legend, the apparition is the ghost of a witch who lived in or near the woods. The third legend suggests that she is the ghost of a young woman whose husband left her to fight in either the Civil War, the War of the Roses or the Napoleonic Wars (depending on which version of the story one encounters) and, during his absence, a group of soldiers killed her infant child and raped her – either killing her or leaving her for dead. In the latter interpretation of the myth, following her encounter with the soldiers the young woman would wander the area in a black cloak, crying out for her murdered child. Say the phrase, ‘Black lady, black lady, I’ve stolen your baby’, and the Black Lady of Bradley Woods shall appear to you…

It’s likely that, like many such stories passed down through generations, this legend was concocted to keep people away from Bradley Woods – perhaps by people using the area for illicit activities who had good reason for frightening away unwanted visitors. However, ask anyone who has roots in the area, and chances are they know someone who has encountered the Black Lady of Bradley Woods in one form or another. Many of these encounters take place outside Bradley Woods itself, on the road nearby, where drivers of passing cars often report having hit something… or someone; but when they stop their vehicles and exit them, with the intention of giving aid to the person their car has struck, they find absolutely nothing. Many similarly described sightings were reported in the local newspaper during the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, and the local police station was reputedly so bombarded with such calls that they would tell distressed motorists that they must have encountered the well-known ghost associated with the area.

It’s likely that, like many such stories passed down through generations, this legend was concocted to keep people away from Bradley Woods – perhaps by people using the area for illicit activities who had good reason for frightening away unwanted visitors. However, ask anyone who has roots in the area, and chances are they know someone who has encountered the Black Lady of Bradley Woods in one form or another. Many of these encounters take place outside Bradley Woods itself, on the road nearby, where drivers of passing cars often report having hit something… or someone; but when they stop their vehicles and exit them, with the intention of giving aid to the person their car has struck, they find absolutely nothing. Many similarly described sightings were reported in the local newspaper during the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, and the local police station was reputedly so bombarded with such calls that they would tell distressed motorists that they must have encountered the well-known ghost associated with the area.

My personal experiences with Bradley Woods have been the opposite of what one might expect. As a very small child, I used to walk to the woods with my mother – no small journey, the walk from my parents’ home being several miles in length. It was a pleasant place, well away from the hubbub of the town. As an older child, myself and my father helped build the fences and kissing gates at the rear of Bradley Woods, as part of a community project initiated by the Humber Wildfowlers, to which my father belonged; those structures are still present but now dilapidated and uncared-for – much like Bradley Woods itself, which in recent years has been cited as a hotspot for drug dealers and ‘dogging’. Recent visits to Bradley Woods with my own family have revealed the evidence of occult practices there – presumably by young people drawn to the woods by its association with the story of the Black Lady of Bradley Woods – including a large pentagram etched into the tarmac pathway just off the car park.

My personal experiences with Bradley Woods have been the opposite of what one might expect. As a very small child, I used to walk to the woods with my mother – no small journey, the walk from my parents’ home being several miles in length. It was a pleasant place, well away from the hubbub of the town. As an older child, myself and my father helped build the fences and kissing gates at the rear of Bradley Woods, as part of a community project initiated by the Humber Wildfowlers, to which my father belonged; those structures are still present but now dilapidated and uncared-for – much like Bradley Woods itself, which in recent years has been cited as a hotspot for drug dealers and ‘dogging’. Recent visits to Bradley Woods with my own family have revealed the evidence of occult practices there – presumably by young people drawn to the woods by its association with the story of the Black Lady of Bradley Woods – including a large pentagram etched into the tarmac pathway just off the car park.

During the 1960s, this council house on the Nunsthorpe estate became infamous as the site of an aggressive haunting. Successive tenants would only stay in the house for a short period of time before requesting to be moved elsewhere. Reports suggest that the house was haunted by an elderly and disfigured man wearing some form of habit – perhaps a monk’s robe. There are numerous houses on the Nunsthorpe estate which have remarkably similarly-described apparitions associated with them. This perhaps has some relationship with the nearby Augustinian abbey and friary, or perhaps the nunnery – or maybe the workhouse and paupers’ cemetery upon which much of the Nunsthorpe estate was built.

Like others in the area, the house was not converted from gas to electricity until the 1960s – 1967, to be precise. My father was employed by the now defunct Yorkshire Electricity Board (YEB) at that time and worked in this house when the conversion was taking place. Tenants had previously reported that the apparition turned the gas taps on at night. Whilst working in the house, employees of the YEB would find that tools would disappear. They initially suspected that these tools were being stolen and the house was placed under close observation – until several of the YEB employees encountered the apparition. One of these was a friend of my father’s who was a firm disbeliever in the supernatural, yet fled from the house after working alone in it one afternoon and refused to return to it – not even to collect his tools and equipment, which he had left behind.